Publications

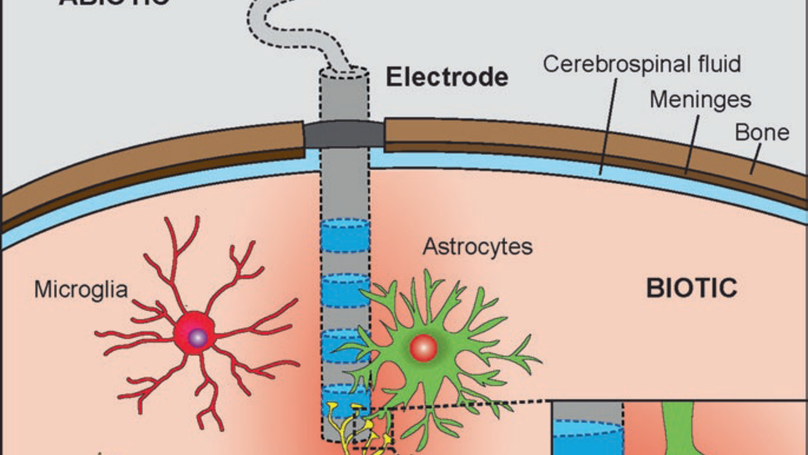

Implanted neural interfaces represent a rapidly growing field, which includes deep brain, peroneal, phrenic, and vagus nerve stimulators, while substantial research efforts have been invested in the development of experimental applications, such as cortical prostheses, retinal prostheses, spinal cord stimulators, etc. The aim of the present chapter is to provide a gap analysis of the field and to debate where future efforts must be directed. The presented gap analysis is intended to informing preventive actions or design decisions for further improvement of the design, fabrication, and exploitation methods of implants. The development of more compliant electrodes remains the main technological challenge. In our view, more efforts in the understanding of the mechanical interactions of an electrode with the surrounding tissue are necessary in order to achieve the next technological breakthrough. The systematic analysis of failure modes of neural interfaces appears to be a key enabling factor for further progress in the field and overall device improvements. Enabling such analysis calls for the implementation of more comprehensive reporting systems, capturing the necessary information.

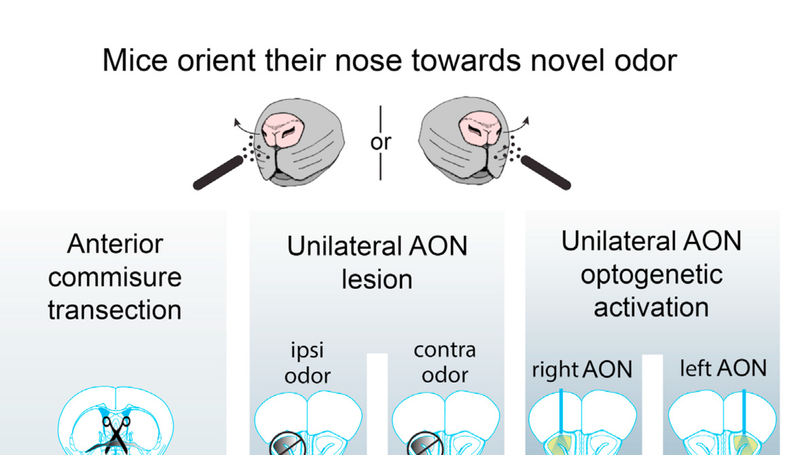

Summary Navigation, finding food sources, and avoiding danger critically depend on the identification and spatial localization of airborne chemicals. When monitoring the olfactory environment, rodents spontaneously engage in active olfactory sampling behavior, also referred to as exploratory sniffing [1]. Exploratory sniffing is characterized by stereotypical high-frequency respiration, which is also reliably evoked by novel odorant stimuli [2, 3]. To study novelty-induced exploratory sniffing, we developed a novel, non-contact method for measuring respiration by infrared (IR) thermography in a behavioral paradigm in which novel and familiar stimuli are presented to head-restrained mice. We validated the method by simultaneously performing nasal pressure measurements, a commonly used invasive approach [2, 4], and confirmed highly reliable detection of inhalation onsets. We further discovered that mice actively orient their nostrils toward novel, previously unexperienced, smells. In line with the remarkable speed of olfactory processing reported previously [3, 5, 6], we find that mice initiate their response already within the first sniff after odor onset. Moreover, transecting the anterior commissure (AC) disrupted orienting, indicating that the orienting response requires interhemispheric transfer of information. This suggests that mice compare odorant information obtained from the two bilaterally symmetric nostrils to locate the source of the novel odorant. We further demonstrate that asymmetric activation of the anterior olfactory nucleus (AON) is both necessary and sufficient for eliciting orienting responses. These findings support the view that the AON plays an important role in the internostril difference comparison underlying rapid odor source localization.